When invited to write a teaching project because my students had nominated me for the Claussen-Simon-Wettbewerb für Hochschulen, my colleague Thomas Eich suggested that I devote a part of the project to the events that happened in 1983 in Hamburg within the field of Euro-Arab cooperation. While working at the Hamburg State Archive, he had come across a reference to a book exhibition that was curated by the Istituto per l’Oriente Carlo Alfonso Nallino in Rome (11–15.04.1983) and that took place at the Atlantic Hotel in Hamburg during the 1983 Euro-Arab Symposium. As a junior professor for Islamic studies in Hamburg who was born in Rome in that year, and given the fact that I had been a member of the Istituto per l’Oriente Carlo Alfonso Nallino for many years, I obviously wanted to know more about the symposium.

In the project application I decided therefore to include a student research trip to the archive of the institute in Rome, to find out more about the cooperation between Rome and Hamburg in 1983. But while in Rome we realized that, in order to understand that cooperation, it was necessary to look at another congress that happened in another Italian city, namely Venice.

Indeed, during the 1970s, different countries within the European Community and the Arab League started to discuss the possibility of establishing a dialogue between members of the two institutions with the aim of working together on a number of topics of common interest.[1] As a result, in the first half of 1974 the Euro-Arab Dialogue was launched.[2] A general Euro-Arab Commission was created to be in charge of taking executive decisions on proposals advanced by specialized Euro-Arab commissions.[3] One of these commissions was in charge of Culture, Labour and Social Affairs and proposed to organize an Euro-Arab symposium devoted to the cultural relations between Europe and the Arab world, a proposal that was supported by the general Euro-Arab Commission. A special committee with representatives from both regions was appointed and, over a number of meetings in 1978, 1981, 1982 and 1983, discussed how to organize the symposium that was going to happen in Hamburg.[4]

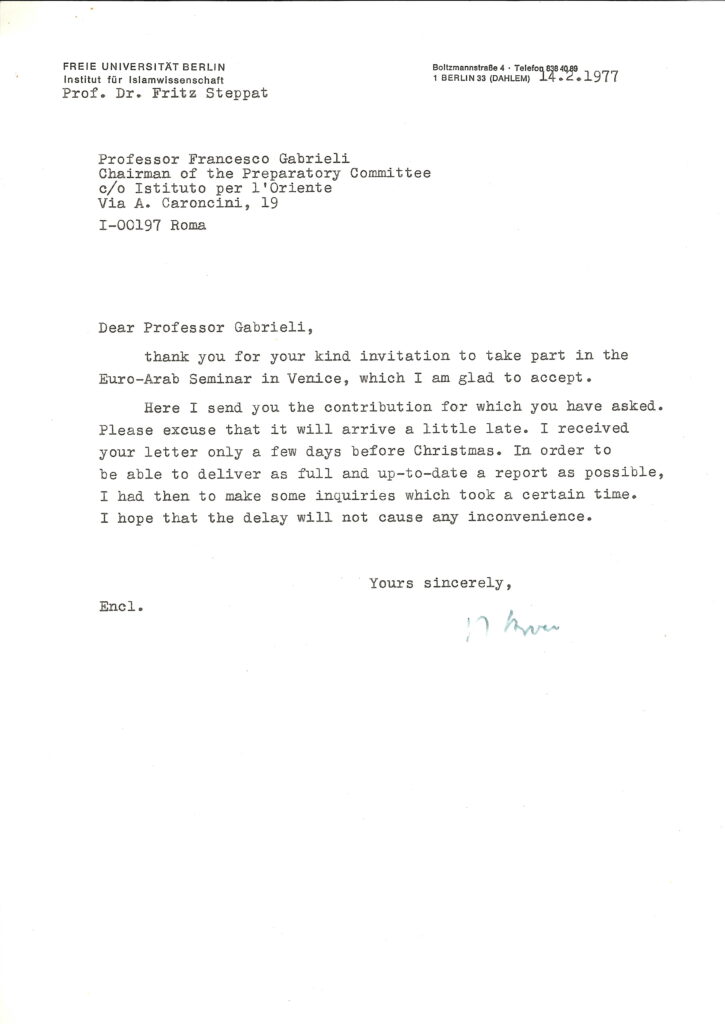

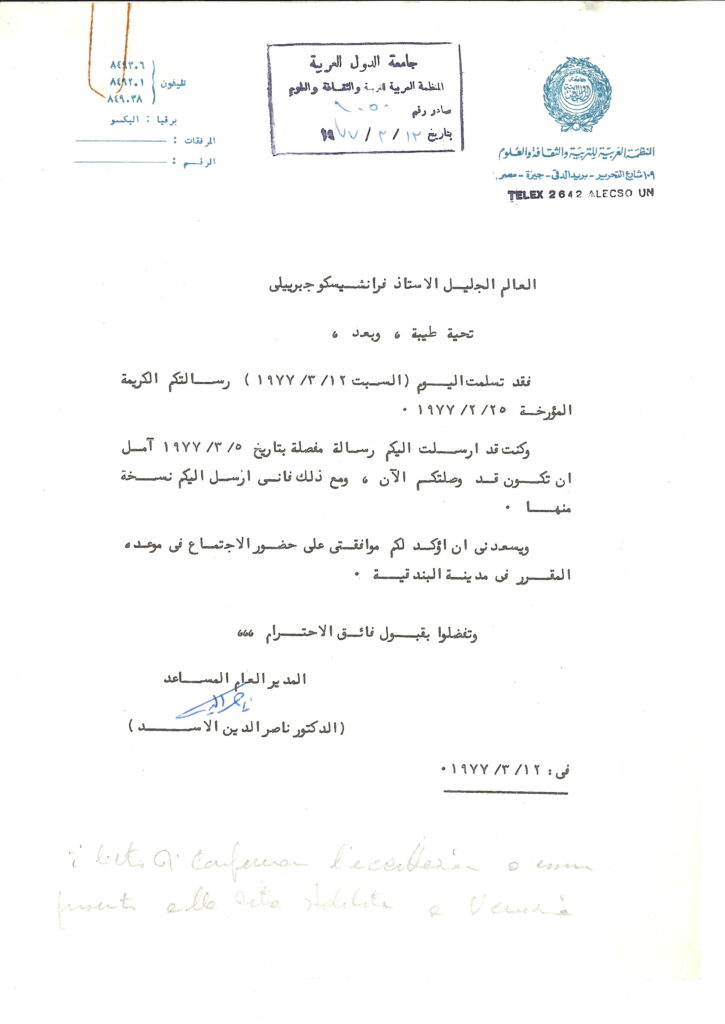

The first meeting organized within the framework of this dialogue was a seminar with the title “Means and Forms of Cooperation for the Diffusion in Europe of the Knowledge of Arabic Language and Literary Civilization”, that took place at the University of Venice between 28 and 30 March 1977.[5] The organization of the seminar was entrusted to the “Seminario di Letteratura Araba” at the Faculty of Foreign Languages at the University of Venice and the Istituto per l’Oriente, an institute founded in Rome in 1921 “by a group of ambassadors, senior civil servants and university professors of Oriental studies, to give Italy a valuable research institution devoted to the Near and Middle East”,[6] today called “Istituto per l’Oriente Carlo Alfonso Nallino”[7] in honour of the Italian Orientalist Nallino, who died in 1938.

Many of the documents of this seminar are still held in the archives of the Istituto per l’Oriente Carlo Alfonso Nallino, and we were able to look at them during a research stay in June 2019 within the framework of this teaching and research project. These documents make clear that the main topic of discussion in the Venice seminar was how to teach Arabic to non-Arabs, a topic that remains topical today. Presenters from different countries discussed how Arabic was taught in Belgium, Denmark, the Federal Republic of Germany and West Berlin, France, Italy, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands. Moreover, speakers addressed the necessity to train Arabic university teachers in French and German universities.

While working at the archive of the Istituto per l’Oriente Carlo Alfonso Nallino, we had a chance to meet Daniela Amaldi, who was one of the participants in that seminar, who showed us the reports and the material that were presented at the meeting in Venice, and the telegrams that were used to invite the participants, something that, in the era of email communication, attracted the attention of all of us.

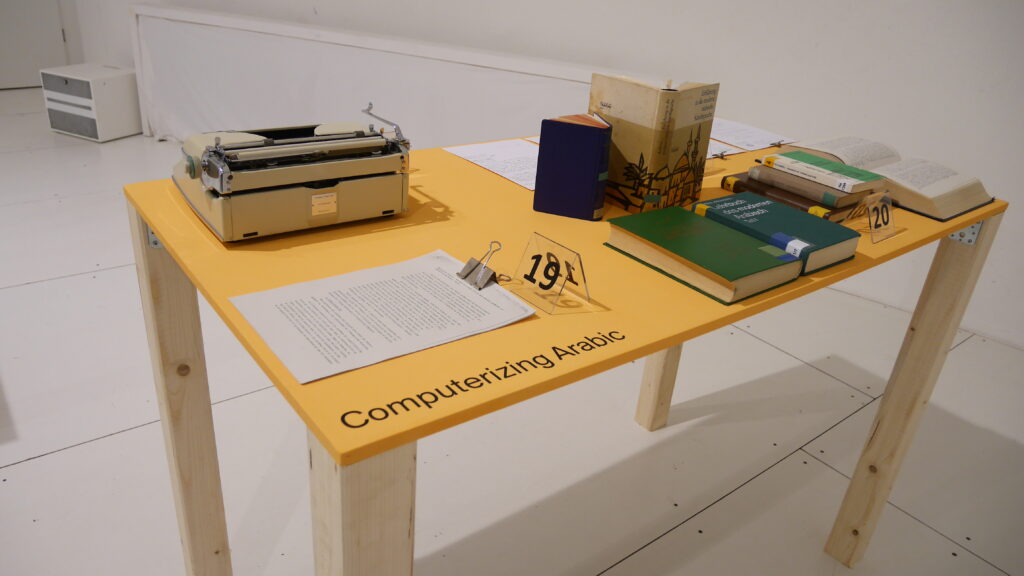

We were particularly struck by the report on the computerization of Arabic texts and also by the debate on how Arabic should be taught: the topics discussed more than 40 years ago are still timely today at seminars where Arabic is taught. This was particularly clear to us when looking at the recommendations drafted at the end of the meeting: for example, according to recommendation no. 10, “in teaching Arabic emphasis must be laid on different linguistic skills; the teaching of Arabic must be linked with Arab-Islamic culture and contemporary Arab issue”, something that is extremely present in light of the discussions on the integration of cultural aspects into the language class.[8] Recommendation no. 18 focused on financial aspects, with the seminar’s participants asking European governments participating in the Euro-Arab dialogue “to exempt the above mentioned institutes (those in Arab and Islamic studies) from cuts in their funds”.[9]

It was, however, only in 1983 that the first (and only) big cultural event in the field of the Euro-Arab dialogue, namely the “Euro-Arab Dialogue Symposium”, took place in Hamburg. The organization of the symposium was coordinated by the Deutsches Orient-Institut, directed by Udo Steinbach, and supported by a group of Arab and European diplomats (such as, for example ambassador for Italy Antonio Puri Purini) and scholars (for example, André Raymond, Professor at the University of Aix-en-Provence).[10]

As pointed out in Nikolai Ballast’s blog post a number of cultural activities were connected to this political event, including an Arabic Film week, where eight films were screened, a number of events devoted to Arab music including groups from Cairo, Tetouan, Damascus, and three exhibitions: one focusing on “The Picture of Arabia in European Literature”, that took place at the Katholische Akademie and was curated by the Herzog August Library in Wolfenbüttel, one on “Arab Art and Islamic Manuscripts”, that included valuable manuscripts from the Chester Beatty Library in Dublin and was held at the Museum für Kunst und Gewerbe, and a book exhibition that took place at the Hotel Atlantic[11] between 11 and 16 April 1983,[12] on which I am going to focus in this blog post.

In this book exhibition, France, Great Britain, Federal Germany, the Netherlands, Greece and Italy exposed books related to the Arab world recently published.[13]

According to reports of witnesses we collected during our stay in Rome, the exhibition was born from an initiative of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which entrusted its execution to the “Center for Italian-Arab Relations”, that was part of the Ministry and was supervised by the then retired ambassador Antonio Puri Purini,[14] who was a member of the organizing committee of the 1983 symposium in Hamburg. The Center for Italian-Arab Relations was located in Rome in via Alberto Caroncini 19, in the same building as the Istituto per l’Oriente Carlo Alfonso Nallino was and still is located. Precisely because of this proximity, the Center asked the Istituto to collaborate on this project, which was then effectively coordinated by the institute, and specifically by the Islamicist Alberto Ventura and the Turcologist Giacomo E. Carretto (d. 2015). Ventura, Carretto and the institute’s librarian contacted all Italian publishers who had recently published books on the Arab-Islamic world in their catalogues. The exhibition was then presented not only in Hamburg but also at the Instituto per l’Oriente.[15]

The list of the books that were included in the exhibition is particularly revealing of what was going on at that moment in Islamic and Middle Eastern studies in Italy: recently published books of leading Italian academics were included, like, for example, Alessandro Bausani’s book on Islam in India or on the Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ,[16] Carmela Baffioni’s work on atomism and antiatomism,[17] Francesco Castro’s publications on Islamic law,[18] Francesco Gabrieli’s works on Arabic poetry,[19] Francesco Beguinot’s grammar of Nefūsī Berberian (a grammar published almost forty years before the exhibition, and on which I studied twenty years later),[20] or Laura Veccia Vaglieri’s[21] Grammar of Arabic language (on which I also studied and which is still used, in a revised version, in many Italian universities).[22] The works of Giorgio Levi della Vida also deserve a special mention.[23] Della Vida was one of the twelve Italian university professors who refused to pledge the oath of loyalty to the Fascist regime and for that reason lost his position at the universit.y[24] The works of Carlo Alfonso Nallino,[25] after whom the institute in Rome was named, were also sent to Hamburg, together with those of Umberto Rizzitano on Arab-Sicilian poetry and his translation of Ṭāhā Ḥusayn’s al-Ayyām.[26]

The list of translated works sent to Hamburg is also very interesting: for example, a translation into Italian of Frantz Fanon’s Les damnés de la terre, published in Italian in 1976;[27] a translation of French sociologist Jacques Berque’s Les Arabes, published in 1978;[28] the book by the Marxist and pan-Arabist sociologist Anwār ‘Abd al-Mālik on Egypte: société militaire;[29] French Marxist sociologist Maxime Rodinsons’s Mahomet;[30] and Noam Chomsky’s Peace in the Middle East? Reflections on Justice and Nationhood[31] were all sent to the exhibition. Besides that, a number of literary works translated from Arabic to Italian were sent to Hamburg: as well as Ṭāhā Ḥusayn, already mentioned were also translations into Italian of many works of the Egyptian author Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm (d. 1987),[32] the Syrian poet Nizār Tawfīq Qabbānī (d. 1998),[33] the Iraqi poet Badr Šākir as-Saiyāb (d. 1964)[34] and the Syrian author and journalist Zakariyyā Tāmir.[35]

This selection confirms on the one hand that one of the strengths of Oriental Studies in Italy has been (and still is) the field of literary and translation studies, with an established tradition that continues up until today. On the other hand, the selection makes clear that pan-Arabist and Marxist sociological approaches to Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies were received in Italy quite early. This is thanks to the efforts of the Italian publishing house Luigi Einaudi, which has played a prominent role: founded in Turin in 1933 by Giulio Einaudi, son of the future President of the Republic Luigi Einaudi, from the very beginning the publishing house distinguished itself for its clear civil, political and intellectual commitment and a clear anti-fascist agenda.[36] Besides academic publishers (in particular the Istituto per l’Oriente, l’Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei and the Istituto Universitario Orientale), Einaudi was certainly the private Italian publishing house that contributed most to the exhibition.

While looking at this list, I realized that it reflects quite faithfully the academic tradition I was exposed to during my time at the University of Naples L’Orientale, where I studied Arabic and Islamic Studies. There is one remarkable absence from this list, though: namely, no translation of Edward Said’s work was sent to Hamburg. However, that should not be surprising: the book published in Italian was not published in Italian until 1991.[37] That it took 13 years to translate Orientalism into Italian is hard to explain if we bear in mind that, for example, Noam Chomsky’s Peace in the Middle East? Reflections on Justice and Nationhood was published in 1974 and already translated into Italian in 1976, but the editorial market certainly has its own rules, which differ (sometimes radically) from academic ones.

It is difficult to assess how the exhibition was received in Hamburg, because this would require another research project. I focused here on the Italian element but it would be interesting to look in the future at the other European publications that were presented at the exhibition too, to better understand what was published, translated and read in the 1980s in relation to the Arab world. What is certain is that the events of 1983 unfortunately are unique in the history of the relations between Europe and the Arab world. While we still have scientific congresses that allow intellectual exchange, I am afraid that the kind of political willingness that made the Hamburg symposium possible no longer exists.

[1] Derek HOPWOOD (ed. of the English version): Euro-Arab Dialogue. The relations between the two cultures. Acts of the Hamburg symposium. April 11th to 15th 1983. London/Sydney/Dover: Croom Helm, 1985, p. 7.

[2] Udo STEINBACH, “III. Die Europäische Gemeinschaft und die arabischen Staaten”. In: Deutsch-Arabische Beziehungen. Bestimmungsfaktoren und Probleme einer Neuorientierung, ed. by Karl Kaiser and Udo Steinbach. München/Wien: Oldenbourg Verlag 1981, pp.185–204, here p. 189.

[3] HOPWOOD 1985, p. 7.

[4] Ibid.

[5] HOPWOOD 1985, p. 315.

[6] Istituto per l’Oriente Carlo Alfonso Nallino, https://www.ipocan.it/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=11&Itemid=2&lang=en. Accessed 16 December 2021.

[7] The institute’s name was changed in honour of one of its founders, Carlo Alfonso Nallino, whose library and house were donated to the Institute by his daughter Maria. Ibid.

[8] See, for example, Ahmad Abdel Tawwab SHARAF ELDIN, “Teaching Culture in the Classroom to Arabic Language Students”, International Education Studies. Vol. 8, No. 2 (2015): 113–120; or the approach behind the website Khallina, see Khallina: ”Who we are”, https://khallina.org/, accessed 16 December 2021.

[9] HOPWOOD 1985, p. 322.

[10] HOPWOOD 1985, pp. 8–9.

[11] HOPWOOD 1985, p. 324.

[12] Istituto per l’Oriente, Dialogo Euro-Arabo, Simposio Euro-Arabo sulle relazioni tra le due civiltà, Elenco dei volumi italiani presentati alla mostra, p. 1.

[13] Istituto per l’Oriente, Lettera del Ministero degli Affari Esteri, D. G. Relazioni Culturali, Uff. III, 9 May 1983. Prot. N. 2126.

[14] Personal email exchange with Alberto VENTURA, 14.06.2019.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Alessandro BAUSANI: L’Islam in India. Tipologia di un contatto religioso. Rome: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 1973 and id., L’Enciclopedia dei Fratelli della Purità. Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 1978.

[17] Carmela BAFFIONI, Atomismo e antiatomismo nel pensiero islamico, con un’appendice di M. Nasti de Vincentis, Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 1982.

[18] Francesco CASTRO, Materiali e ricerche sul Nikāḥ al-Mut‘a. I-Fonti imāmite. Rome: Accademia nazionale dei Lincei, 1974.

[19] Francesco GABRIELI, Gli Arabi nel Mediterraneo. Rome: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 1970; id., Studi su al- Mutanabbī. Rome: Istituto per l’Oriente, 1972; id., Viaggi e Viaggiatori Arabi. Florence: Sansoni, 1975.

[20] Francesco BEGUINOT, Il Berbero Nefûsi di Fassâto. Rome: Istituto per l’Oriente, 1942.

[21] She worked for the Italian Ministry of Colonies.

[22] Laura VECCIA VAGLIERI, Grammatica teorico-pratica della Lingua araba. Rome: Istituto per l’Oriente, 1959. The Grammar has also been published for the Istituto per l’Oriente in a revised edition by Maria Avino in 2011.

[23] Giorgio Levi DELLA VIDA, Arabic Papyri in the University Museum in Philadelphia (Pennsylvania). Rome: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 1981; id., Note di storia letteraria arabo-ispanica. Rome: Istituto per l’Oriente, 1971.

[24] He then had to flee to the United States, where he taught at the University of Pennsylvania between 1939 and 1943, and then again later between 1946 and 1948. More on that can be found in Helmut GOETZ, Il giuramento rifiutato. I docenti universitari e il regime fascista. Florence: La nuova Italia, 2000.

[25] Carlo Alfonso NALLINO, Chrestomathia Qorani Arabica. Rome: Istituto per l’Oriente, 1963; id., Raccolta di Scritti editi e inediti. Rome: Istituto per l’Oriente, voll. II, III, IV: 1940–1942.

[26] Umberto RIZZITANO, Un compendio dell’antologia dei poeti arabo-siciliani intitolata ad-Durrah al- Ḫatīra min Šu‘arā’ al-Ğazīra di Ibn al-Qaṭṭā‘ “Il Siciliano” (433-515 Eg.). Rome: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 1958; L’islam maghribino, Rome: Accademia Nazionale dei Lincei, 1974; transl. and ed. by Umberto RIZZITANO, Ṭāhā ḤUSAIN, I giorni. Naples: Istituto Universitario Orientale, 1964.

[27] Frantz FANON, I Dannati della Terra. Turin: Einaudi, 1976.

[28] Jacques BERQUE, Gli Arabi. Turin: Einaudi 1978.

[29] Anouar ABDEL-MALEK, Esercito e Società in Egitto 1952–1967. Turin: Einaudi 1967.

[30] Maxime RODINSON, Islam e Capitalismo. Saggio sui rapporti tra economia e religione. Turin: Einaudi, 1968.

[31] Noam CHOMSKY, Riflessioni sul Medio Oriente. Turin: Einaudi, 1976.

[32] Tawfīq AL-ḤAKĪM, La Gente della Caverna, ed. and transl. Umberto RIZZITANO. Rome: Centro per le Relazioni Italo-Arabe, s.d.; id., O tu che Sali sull’albero…, ed. and transl. Adalgisa DE SIMONE. Rome, Istituto per L’Oriente 1971; id., La prigione della vita, ed. by Giuseppe BELFIORE. Rome, Istituto per L’Oriente 1976; id., Shams an-Nahār, ed. and transl. Vincenzo STRIKA. Rome: Istituto per L’Oriente 1974; id., Un sultano in vendita, ed. and transl. Virginia VACCA. Rome: Istituto per L’Oriente, 1964.

[33] Nizār QABBĀNĪ, Poesie, ed. and transl. Giovanni CANOVA et al. Rome: Istituto per l’Oriente, 1976.

[34] Badr Šākir AS-SAIYĀB, Poesie, ed. and transl. Paolo MINGANTI. Rome: Istituto per l’Oriente, 1968.

[35] Zakariyyā TĀMIR, Racconti, ed. and transl. Eros BALSIDDERA. Rome: Istituto per l’Oriente, 1979.

[36] It is no coincidence that the publishing house and Giulio Einaudi himself were targeted by the regime. In 1935 Einaudi was first arrested and then sent to confinement. On the fascinating history of this publishing house, see Luisa MANGONI, La casa editrice Einaudi dagli anni Trenta agli anni sessanta. Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 1999.

[37] Edward SAID, Orientalismo, transl. Stefano GALLI. Turin: Bollati Boringhieri, 1991.